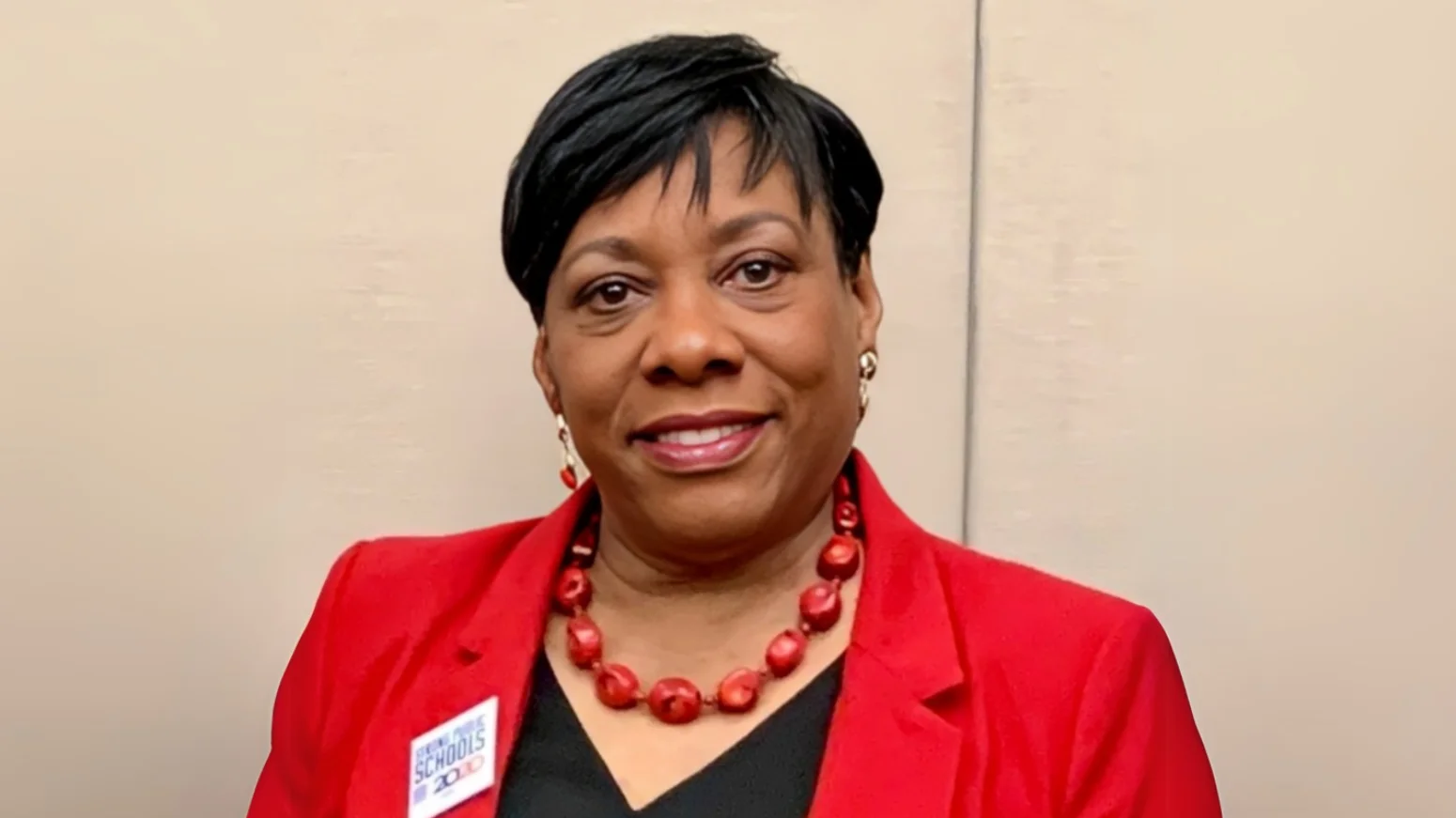

Denise Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parents Attorneys and Advocates (COPAA) | COPAA

Large-scale reductions at the U.S. Department of Education have raised concerns among advocates and experts about the future of special education services for students with disabilities. These cuts follow through on plans outlined in the conservative policy guide “Project 2025,” as pursued by the Trump administration.

Denise Marshall, CEO of the Council of Parents Attorneys and Advocates (COPAA), expressed concern that progress made since landmark legislation in the 1970s and 1990s could be undone quickly. “It does seem like so far ago, but right now we’re witnessing all we accomplished could go away in the blink of an eye,” she said.

Secretary of Education Linda McMahon defended the cuts, stating, “Closing the Department does not mean cutting off funds from those who depend on them—we will continue to support K-12 students, students with special needs, college student borrowers, and others who rely on essential programs.” She added that accommodations such as those under IDEA and individual education programs (IEPs) would remain for approximately 7.5 million students nationwide.

However, disability rights lawyer Eve Hill argued that eliminating much of the department’s workforce undermines these guarantees: “If there's no one to do the work, then you have gotten rid of them. They’re reducing our rights to pieces of paper.”

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, over 1 million more students received special education accommodations in 2022–2023 compared to a decade earlier—rising from 6.4 million to 7.5 million. This represents about 15 percent of all public school students.

The federal government currently allocates $15 billion annually for special education across states, supporting teachers, aides, early intervention programs, and therapists. Many advocates doubt whether a reduced Department workforce can effectively oversee or distribute these funds.

“You end up with no oversight and no way to distribute the resources,” said Susan Popkin, co-director of the Disability Equity Policy Initiative at Urban Institute. She noted disparities between states’ ability or willingness to provide services if left largely unregulated: “Some states will have funding and services ready to go and others won’t do anything at all, so we’ll have huge holes across the country.”

There is also discussion about converting IDEA funding into block grants—a move that could allow states discretion over which disabilities receive priority for federal support. Carrie Gillispie from New America voiced concern: “They may prioritize it in odd or harmful ways… everything we've seen in the president's proposal and other rhetoric leading up to now is making people worried they will block grant it.”

Early intervention programs—which help address issues before children require more intensive special education—are also at risk due to both Departmental cuts and potential reductions in Medicaid funding. Gillispie said: “It’s already underfunded, it’s already strained… Demand keeps rising for young kids with disabilities; there's more young children being identified, so demand is going up with supply going down.”

With fewer federal staffers available for guidance or technical assistance, confusion over legal compliance may increase among state officials and educators. Gillispie noted that new state directors lack experienced contacts within ED: “Parents, educators and state administrators rely on ED [the Education Department] for a lot of help... [ED officials] have institutional knowledge you can't read from a textbook.”

Complaints related to violations under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act or IDEA are typically handled first locally before escalating federally. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which processes many such complaints—over one-third related to disabilities—has faced major staffing reductions this year.

Hill expects families will increasingly turn to private lawyers as OCR becomes overwhelmed: “I think there will be more problems; there just won't be anywhere to go with them… But there are not enough of us, so people will end up having their educational rights taken away.” David Bateman, a retired professor specializing in special education law, pointed out that hiring private counsel is often financially out-of-reach for most families.

Advocates recommend parents contact local representatives and collaborate with schools while leveraging organizations like COPAA or forming parent-teacher associations focused on special education needs.

“Everyone can take some level of action to reverse this and it's important to be loud about it,” Marshall said. Popkin added: “Things are different than the earlier eras; there's a lot of strong advocacy groups for disabilities and parents are always motivated to protect their kids… If we’re not going to protect our children, who will we protect?”

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up